Kenneth O. May Prize in the History of Mathematics

Kenneth O. May was a mathematician and historian of mathematics of great vision. He recognized the need for a unified international community of historians of mathematics and worked tirelessly over the last nine years of his life to effect such a change.

In 1968, May spearheaded a discussion that ultimately led in 1971 to the founding of the International Commission on the History of Mathematics (ICHM) for the encouragement and promotion of the history of mathematics internationally. As the first Chair of the new ICHM, May worked in two key ways to achieve these goals. In 1972, he coordinated the publication of the first World Directory of Historians of Mathematics, in an effort bring historians of mathematics more easily into contact with one another. Then, in 1974, he brought out the first volume of Historia Mathematica, the international research journal for the history of mathematics overseen by the ICHM. As Historia's first editor, May worked tirelessly to support and to hone the research efforts of historians of mathematics around the world.

Following May's death in 1977, the ICHM sought a suitable means by which to honor the memory of this remarkably selfless contributor to the international community of historians of mathematics. The result was the Kenneth O. May Prize given for outstanding contributions to the history of mathematics and first awarded in 1989 to Dirk J. Struik and Adolf P. Yushkevich on the occasion of the 18th International Congress of History of Science in Hamburg and Munich. In 1993, the ICHM commissioned the Canadian sculptor, Salius Jaskus, to design in bronze the Kenneth O. May Medal as part of the Kenneth O. May Prize.

The next Kenneth O. May Medal and Prize will be awarded in 2025 at the 27th International Congress of History of Science and Technology in Dunedin (New Zealand)

To date, the following distinguished historians of mathematics have been recognized for their work through the presentation of the Kenneth O. May Prize and Medal:

27th International Congress of History of Science and Technology, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2025

Jan Hogendijk (The Netherlands)

Jan Hogendijk

Jan Hogendijk

By combining meticulous textual analysis with an in-depth command of technical mathematical content, Jan Hogendijk is a master at deciphering historical texts. In this way he has illuminated the history of mathematics in the medieval Islamic world, produced “a series of valuable studies on traces of lost works of Greek geometers in Arabic sources” as well as deep studies on the reception of this tradition in early modern Europe.

Gerald Toomer called Hogendijk’s PhD thesis “simply the best dissertation in the history of mathematics that I have ever seen. I am particularly impressed by Mr. Hogendijk’sknowledge and understanding of the methods of ancient and medieval conics, which surpasses that of everyone since the time of Zeuthen, and is astonishing in one so young”.

Hogendijk is a selfless servant of the field, for instance as managing editor of Historia Mathematica (1996-1999), Secretary of the International Commission for the History of Mathematics (2002-2005), and President of the International Commission on History of Science and Technology in Islamic Civilizations (2010-2013).

Throughout his career, Hogendijk has been a beacon of integrity, who has contributed to confidence in the professionalism and scholarly quality of the field. One mark of recognition of Hogendijk’s impeccable commitment to the highest standards of integrity was his appointment to the Landelijk Orgaan Wetenschappelijke Integriteit - the national committee for arbitrating academic research integrity disputes at Dutch universities.

As a teacher Hogendijk is highly valued. For many years he taught not only history of mathematics but also for instance the large lecture course on calculus for all mathematics bachelor students. Generations of students fondly recall the care and commitment that he brought to this role, as well as his historical excursions such as singing the power series of trigonometric as encoded in poetry in 15th-century Kerala school mathematics. Hogendijk received the university-wide Teacher of the Year award at Utrecht University in 1997.

Hogendijk has organised History of Mathematics workshops in many European, Middle-Eastern and even Asian countries. In these workshops, the audience gets hands-on experience with a model of a historical mathematical object, e.g., an astrolabe or a mathematical table. This hands-on approach is a very effective way to engage people who do not know much about history and/or mathematics, even school children. It often leads to interesting discussions, and it functions as a way to reconnect the people of the Middle East to their own local scientific traditions. Typical of Hogendijk’s attitude is that he not only organises these workshops himself: he is most keen to teach others how to organise them. Thus, he does all he can to promote the joy and understanding of History of Mathematics.

A particularly important feature of Hogendijk’s contribution to the history of mathematics community is his generous support of junior scholars. At Utrecht University he led a small but lively history of mathematics research group, where he supervised a number of PhD students. As a postdoc at Neugebauer’s History of Mathematics Department at Brown University in the early 80s, he saw a research institute of the highest quality dwindle and ultimately shut down. This impressed on him the importance of not only doing excellent research for oneself but also the responsibility of the scholar as a steward of the field. He was thus mindful to leave his own research group in a secure position upon his retirement and not to let it lapse as the Brown department did. He went to great lengths to achieve this, and he succeeded. This did not come for free, but through his own selfless work and sacrifices on behalf of others.

27th International Congress of History of Science and Technology, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2025

David Rowe (Germany)

Since moving from the U.S. to Germany in the early 1990s, David Rowe has been one of the leading experts on the mathematics of the Göttingen world centre, especially for the years from Felix Klein’s appointment in 1886 to the destruction of the centre by the Nazis in 1933. He has published substantially on Klein’s mathematics, in particular on the geometrical aspects of his work (line geometry, algebraic geometry, relationship to group and invariant theories, non-Euclidean geometry, relativity). He has also discovered much new about the beginnings of Klein’s scientific career and the role of his teacher Plücker in Bonn, particularly with regard geometric models in the development of mathematics. Rowe has done biographical work on leading mathematicians in Göttingen (Hilbert, E. Noether, Dehn, Blumenthal) and on mathematicians and physicists associated with them (Lie, Hurwitz, Einstein, F. Noether).

Since moving from the U.S. to Germany in the early 1990s, David Rowe has been one of the leading experts on the mathematics of the Göttingen world centre, especially for the years from Felix Klein’s appointment in 1886 to the destruction of the centre by the Nazis in 1933. He has published substantially on Klein’s mathematics, in particular on the geometrical aspects of his work (line geometry, algebraic geometry, relationship to group and invariant theories, non-Euclidean geometry, relativity). He has also discovered much new about the beginnings of Klein’s scientific career and the role of his teacher Plücker in Bonn, particularly with regard geometric models in the development of mathematics. Rowe has done biographical work on leading mathematicians in Göttingen (Hilbert, E. Noether, Dehn, Blumenthal) and on mathematicians and physicists associated with them (Lie, Hurwitz, Einstein, F. Noether).

Rowe’s 1994 monograph The Emergence of the American Mathematical Research Community, 1876-1900, published jointly with Karen Parshall, was a milestone in the study of German-American mathematical relations and remains an indispensable source. In his work, Rowe is often also interested in methodological, sociological and political questions. For example, he has contributed significantly to the understanding of mathematics as an “oral culture” and has analysed academic anti-Semitism in mathematics. In recent years, Rowe has also increasingly worked on the role of the crisis of foundations in mathematics around 1900 and on the understanding of the concept of modernity, partly in critical discussion of Herbert Mehrtens’ theses.

Even as an emeritus professor (since 2015), Rowe remains as active as ever in research. His wide-ranging monograph Felix Klein. The Erlangen Program, was published this year (2025).

Rowe has made significant contributions to the development of history of mathematics as a discipline. Since his appointment to the University of Mainz in 1992, he has developed the “History of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Department” there into a leading international institution, playing a major role in the training of a new generation of historians of mathematics. Among his 10 Ph.D. students and the two habilitations supervised by him are historians of mathematics who are today among the leading representatives of the field, for example Moritz Epple, Annette Imhausen, and Volker Remmert. This impact of Mainz is ongoing, particularly in cooperation with neighbouring institutes in Wuppertal and Frankfurt.

Rowe was Managing Editor and Editor-in-Chief of Historia Mathematica for 1990-1995. As Column Editor of “Years Ago” of The Mathematical Intelligencer (2002-2016), he has also had an impact on wider circles of historically interested mathematicians. He was an Associate Editor of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, and general editor (with J. W. Dauben) of the 6-volume, A Cultural History of Mathematics (2024).

Rowe has organized numerous international workshops on the history of mathematics, including one at Vassar College (1988), the Summer Workshops on History of Modern Mathematics Göttingen (1990-1993), and eight historical workshops at the Mathematical Research Institute in Oberwolfach between 1998 and 2020. The Proceedings of the “Symposium on the History of Modern Mathematics” at Vassar (1988), organized with John McCleary, are still a frequently used source for the history of mathematical ideas. With his workshops around 1990 Rowe was among those who were instrumental in the formation of a reunited German history of mathematics community.

Since his retirement in 2015, Rowe has published increasingly (partly together with Mechthild Koreuber) on the biography and the work of Emmy Noether. A particular highlight is the suggestion of and advisory work for a play about Noether, which has been performed by the “Portrait Theatre Vienna” in various European and American cities since 2019.

Just recently (in 2024) Rowe has underlined his constant and selfless willingness to help and his sense of responsibility for the community as a whole by translating into English a biography of Felix Hausdorff, originally written in German by Egbert Brieskorn and Walter Purkert

26th International Congress of History of Science and Technology, Prague, Czech Republic (online due to pandemic), 2021

Sonja Brentjes (Germany)

Sonja Brentjes

Sonja Brentjes

is a renowned historian of science of Islamicate societies with a strong focus on the mathematics of medieval Islam. She has held prestigious positions at notable institutions, including the Institute for the History of Science at Goethe University Frankfurt, the University of Oklahoma, the Aga Khan University Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations, the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, the University of Seville, and her current position at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, where she has been since 2012.

Brentjes has published extensively on different topics in the history of mathematics. A recent monograph, Teaching and Learning the Sciences in Islamicate Societies (800 - 1700) (Brepols, 2018), is a ground-breaking survey of the main teaching texts and their contents as well as forms of classification of knowledge that was the basis of intellectual life in the Islamic Near East and has made an enormous contribution to our knowledge in this area. She has also shown strong leadership in her scholarly response to the international public outreach initiative “1001 Inventions”, and directed the scholarly community to provide critical feedback, which she collected, edited and published in 2016. From 2016–2020, she was the leader of a team of international scholars who are collecting and curating a database of images produced by Eurasian and North African premodern cultures of inquiry related to visualizing the heavens. In addition to broad thematic studies, she works on editing and translating primary sources and is currently working on a new translation of The Book on the Balance of Wisdom by ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Khazini, a 12th-century astronomer and mathematician.

26th International Congress of History of Science and Technology, Prague, Czech Republic (online due to pandemic), 2021

Christine Proust (France)

Christine Proust

Christine Proust

is professor emeritus and senior researcher at the SPHERE laboratory, CNRS, and Université de Paris. Proust’s work on calculation techniques, such as her work on a Mesopotamian abacus, elucidated basic mathematical practice and enables us to understand this mathematical culture as distinct from our own. Her work on mathematics at Old Babylonian Nippur changed how we view Babylonian mathematics, affording a better understanding of how numbers, metrology, and calculation were learned and exploited in this distant and unique mathematical culture. Her research on numbers and metrology, produced a more transparent methodology than seen previously, which in turn fosters greater access to Babylonian mathematics by both Assyriologists and by historians of mathematics. Her work on scholars and scholarship in the Mesopotamian city of Uruk, helps us understand how knowledge was produced, circulated, and preserved within an ancient society. Finally, her research into historiography helps us better understand the impact and shortcomings of past research into the history of mathematics.

Proust has developed numerous partnerships to promote research into the history of Babylonian mathematics. She has collaborated to produce new tools to research Babylonian mathematics, and worked closely with researchers from all over the world going beyond her own academic environments to support less experienced researchers and researchers from outside her own academic community. Since the 2000’s Proust has worked with the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative to provide open-access images and editions of cuneiform texts and in the process has pioneered how numbers and metrological systems can be digitalized.

As a teacher, Proust has and will have a lasting impact on both Assyriology and the history of mathematics. She has taken students in ancient geometry, ancient algebra, historiography, education, and much more. She has for years now presided over a group interested in the history of mathematics from all across the globe – from Brazil to Germany, the US to the UK – that meets regularly in person and online to better understand Babylonian mathematics and exchange ideas on this subject

25th International Congress of History of Science and Technology in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2017

Eberhard Knobloch (Germany)

Eberhard Knobloch

Born in 1943, Eberhard Knobloch studied mathematics, classical philology, philosophy, and history of science and technology. In 1972 he completed his PhD in history of science and technology, and in 1976 he passed the habilitation in this subject. Since 1981 he has been Professor of History of Science and Technology at the Technical University of Berlin, since 2002 Academy Professor at the University and at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities (the former Prussian Academy of Sciences). He has promoted the history of mathematics as head of its most important societies, including the ICHM, and as editor of its publication series and journals including Historia Mathematica. Knobloch was President of the International Academy of the History of Science from 2005 to 2007 and President of the European Society for the History of Science from 2006 to 2008. His written record is truly impressive, amounting to some 300 books or papers on history or philosophy of science and technology

Knobloch started his career as a historian of mathematics and science with his pioneering studies on the mathematical work of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The latter has remained a central point of reference for his scholarly research. He has carried out a series of studies of Leibniz’s theory of determinants and contributions to actuarial mathematics, as well as an impressive number of ground-breaking articles on several aspects of the mathematical work of Leibniz. Particularly notable is his critical edition with commentary of Leibniz’s “De quadratura arithmetica circuii ellipseos et hyperbolae cujus corollarium est trigonometria sine tabulis,” published in 1993 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht). Some of Knobloch’s insights into Leibniz’s analysis are presented at a more general level in his article “Galileo and Leibniz: Different Approaches to Infinity” (Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 54 (1999), pp. 87–99). Knobloch established series 7 and 8 of the Leibniz-Edition and served as its editor for many years. It is no exaggeration to say that he has gained an international reputation as a leading expert for the edition of works of scientists in the period from 1600 to the present. Besides the edition of Leibniz’s works he was involved in the edition of the works of the astronomer Johannes Kepler and in the edition of the letters of the German natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt. As a historian of mathematics Knobloch has not only published on a broad range of topics and figures in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but also made important contributions to the history of probability theory, error theory, determinant theory and to measurement and integration theory in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Kenneth O. May Prize and Medal, 2017

Roshdi Rashed (France)

Roshdi Rashed is an eminent historian of mathematics specializing in Islamic mathematics and its relation with Greek mathematics on the one hand, and influence on modern mathematics on the other hand. He has shed considerable light on the work of several important Islamic mathematicians, including Banū Mūsā, Ibn Qurra, Ibn Sīnā, al-Khāzin, al-Qūhī, Ibn al-Samh, Ibn Hud, and especially Ibn al-Haytham, who stands out as a towering figure of medieval Islamic mathematics. Rashed discovered, edited and translated a large number of manuscripts and through insightful analysis of their contents, has brought out their importance from the point of view of development of mathematics, their intricate relation with the Greek antecedents, and their influence and impact on the later European mathematics. The work has led to a sea change in our understanding of the significance of Islamic contributions, especially from what has now come to be viewed as the golden era of Islamic mathematics. It has also thrown new light on various aspects of Greek mathematics, especially of Apollonius and Diophantus, and their interrelation.

Born in 1936, Roshdi Rashed has spent the most part of his career affiliated with Paris Diderot University (Paris 7), as a researcher sponsored by the French CNRS. Among his several distinctions one may mention the CNRS Bronze Medal (1977), the distinction of Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (1989) awarded by the President of the French Republic, the Alexandre Koyré Medal (1990), the Prize and Medal from the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (1999), and the King Faisal International Prize (2007). He has also received several honors from Arabic countries. He has about 40 books and more than 100 papers to his credit. He is a member of several academies, the chief editor of the journal Arabic Sciences and Philosophy: a Historical Journal (Cambridge University Press), and of the collections Histoire des Sciences Arabes (Beyrouth) and Sciences dans l’histoire (Blanchard, Paris). He is a member of scientific committees of the journals Revue de Synthèse (France), Bollettino di storia delle scienze matematiche (Italy), Istoriko-Matematicheskie Issledovaniya (Moscow), Islamic Studies (Pakistan) and Le Journal Scientifique Libanais (Beyrouth).

24th International Congress of History of Science and Technology in Manchester, UK, 2013

Menso Folkerts (Germany) and Jens Høyrup (Denmark)

23rd International Congress of History of Science and Technology in Budapest, Hungary, 2009

Ivor Grattan-Guinness (UK) and Rhada Charan Gupta (India)

Click here for the report

The Kenneth O. May Prize and Medal was awarded to Professor R.C. Gupta at the closing Ceremony of the International Congress of Mathematics on August 27, 2011 in Hyderbad, India. The presentation was made by Kim Plofker (See video and press release)

Valedictory Symposium on the occasion of the retirement of Henk Bos, Utrecht, Netherlands, June 30, 2005

Henk Bos (Netherlands)

Click here for the report.

21st International Congress of History of Science and Technology in Mexico City, Mexico, 2001

Ubiratn D'Ambrosio (Brazil) and Lam Lay Yong (Singapore)

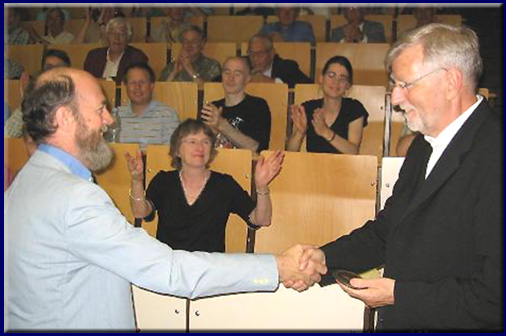

The image on the left shows Ubiratan d'Ambrosio receiving the Kenneth O. May Medal at the International Congress on History of Science and Technology in Mexico City, Mexico, in 2001.

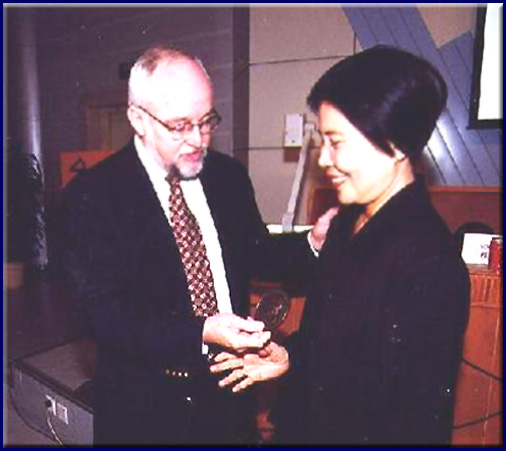

The image on the right shows Joseph Dauben presenting the fourth Kenneth O. May Medal to Lam Lay Yong at the International Congress of Mathematics in Beijing, China, 2002

Click here for the report

20th International Congress of History of Science in Liege, Belgium, 1997

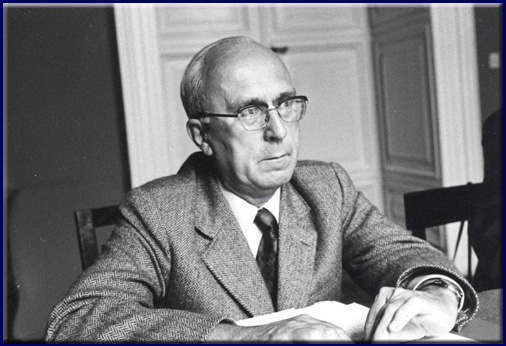

René Taton (France)

19th International Congress of History of Science in Zaragoza, Spain 1993

Christoph J. Scriba (Germany) and Hans Wussing (Germany)

The second Kenneth O. May Medal presented by Joseph Dauben to Christoph Scriba and Hans Wussing

18th International Congress of History of Science in Hamburg and Münich, Germany, 1989

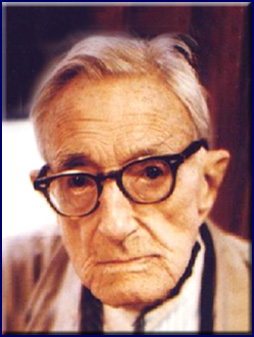

Dirk J. Struik (United States) and Adolf P. Yushkevich (Soviet Union)

.jpg)